Here's a summary version of the

talk I gave at the University of Ottawa on November 23rd (an updated and somewhat expanded version of the

presentation I made at Laval University in October):

The Communications Security Establishment: What do we know? What do we need to know?

Some of the people here today know a great deal about the Communications Security Establishment, but it is likely that a lot of you do not know a lot about it, so I'd like to begin with some background information about the role, origins, and evolution of the agency. I’ll then describe what we know and don’t know about whether CSE monitors Canadians in the course of its operations. Finally, I’ll wrap up with some suggestions on how to improve transparency about CSE and its operations.

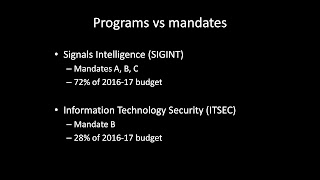

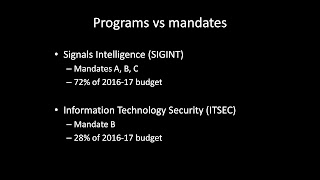

CSE is Canada’s national cryptologic agency. It has two programs: SIGINT and ITSEC.

(The photo shows the Edward Drake Building, CSE's new headquarters.

Source.)

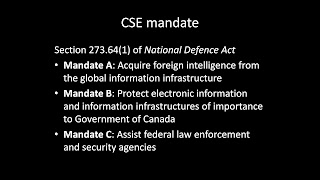

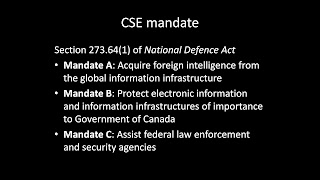

The agency has a three-part mandate laid out in the

National Defence Act.

The SIGINT program addresses all three elements of CSE's mandate and accounts for about $435 million of the agency's $605 million budget for FY 2016-17, while the ITSEC program is focused on Mandate B and accounts for about $170 million.

The agency recently celebrated its

70th birthday, but its origins lie in the signals intelligence co-operation initiated between the Western allies during the Second World War.

(CSE's first headquarters was located on the third floor of the La Salle Academy, a Catholic boys school in downtown Ottawa, shown on the left. The facility had previously been occupied by one of CSE's wartime predecessor organizations, the Joint Discrimination Unit.)

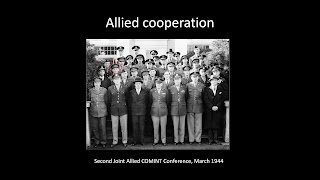

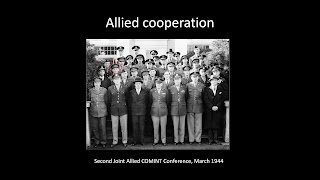

Although Canada was a very small player in Second World War SIGINT, it participated in the planning that allocated intercept and processing tasks among the allies and shared in the intelligence output. This deep integration of SIGINT activities laid the foundations for the very close co-operation that has persisted to the present.

Lt-Col Ed Drake is circled in red in this photo from a 1944 planning conference. (

Source.) Five other Canadians and the British cryptanalyst supplied to Canada to run the Examination Unit (the civilian in the back row) are also in the photo.

The U.S. and U.K. agreed to continue SIGINT cooperation into the post-war era even before the war ended, with the new primary target to be the Soviet Union. The BRUSA (later renamed UKUSA) agreement, the founding document of the post-war partnership, was negotiated in the fall of 1945 and signed on 5 March 1946. Canada and the other Dominions of the British Empire were not signatories of the agreement, but provision for their participation was written into it.

By the time CSE, known originally as the Communications Branch of the NRC, was formally established on 1 September 1946, its position as junior member of a multinational SIGINT conglomerate had thus already been determined.

The CBNRC was transferred to the Department of National Defence and renamed the Communications Security Establishment on 1 April 1975. In November 2011 it became a stand-alone agency, still under the Minister of National Defence but no longer a part of the department.

The radio intercept stations that supplied CBNRC/CSE are operated by the military, currently the Canadian Forces Information Operations Group.

Oh, and there's Ed Drake again.

We turn now to an extremely abbreviated history of the organization:

There was a Cold War, during most of which CSE focused almost exclusively on the Soviet Union.

Then the Cold War ended, and CSE found new targets, principally diplomatic and economic.

And then

this happened, and CSE's focus shifted once again.

Which brings us up to the present.

Since 9/11, counter-terrorism has been CSE's top priority, with Support to Military Operations also of increased importance.

The advent of the Internet also had a dramatic effect on the agency's operations, opening whole new avenues for SIGINT operations, including Computer Network Exploitation activities to access "data at rest" on target computer systems.

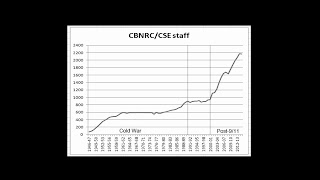

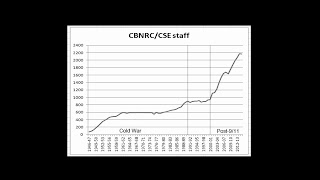

The post-9/11 era saw the greatest period of growth in CSE's history. Now apparently stabilized at a staff of about 2100–2200, CSE has 2.3 times as many employees as it had prior to 9/11 and 3.5 times as many as it had through most of the Cold War.

Its budget has also grown dramatically since 9/11. At $605 million in FY 2016-17, CSE's current budget is 4.5 times as high in inflation-adjusted dollars as its pre-9/11 budget. (The spike to nearly $900 million in 2014-15 was the result of a one-time $300 million payment made when the agency's new headquarters was completed.) By comparison, CSIS’s $594 million budget is 2.6 times as high as its pre-9/11 budget.

Canada's legacy radio intercept stations—Alert, Gander, Masset, and Leitrim— are still in operation, the first three now operated remotely from Leitrim...

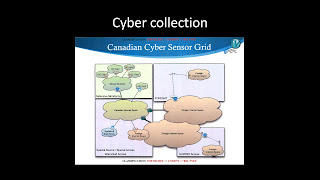

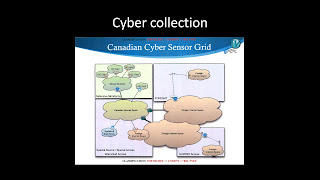

...but the real SIGINT action now takes place in cyberspace. (

Source.)

A lot of current SIGINT collection is “special source” collection – obtained by tapping the traffic carried on the fibre optic cables and high-speed routers that form the physical infrastructure of cyberspace, sometimes with, sometimes without the cooperation of the companies that own and operate it. This graphic shows just one company’s worldwide network.

The Internet quickly became the primary hunting ground of CSE and its SIGINT partners, and they undertook to

Master the Internet.

According to CSE, the shift towards the Internet as hunting ground has actually increased the importance of the Five Eyes partnership.

CSE’s dependence on its allies, and in particular on the U.S., makes the election of Donald Trump – already potentially huge for Canadian foreign and defence policy – even more significant. If President Trump does even half of the things he has promised (torture, war crimes, mass surveillance…) it will represent a crisis for intelligence-sharing with the U.S.

I don’t have a detailed set of suggestions for how Canada might respond, but at a minimum we would have to revisit CSE's

Ministerial Directive on Framework for Addressing Risks in Sharing Information with Foreign Entities, which currently excludes Canada’s Five Eyes partners.

Another aspect of the global nature of Internet traffic is that mixed in among the traffic that CSE and its allies seek to monitor is the Internet traffic of Canadians.

(This graphic depicts the undersea fibre optic cables that carry a large proportion of the world’s Internet traffic.

Source.)

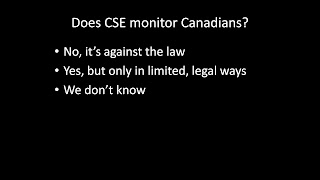

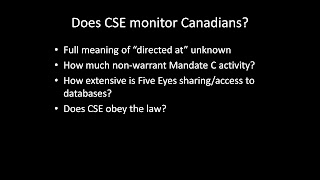

The intermingling of Canadian Internet traffic with that of the rest of the world means that CSE encounters Canadian communications even when it is trying not to do so. And this raises an important question: Does CSE monitor Canadians?

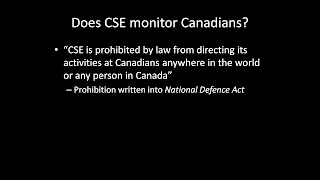

I have three answers to that question.

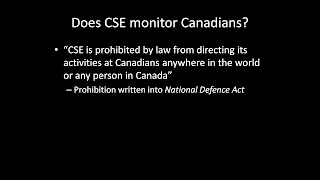

The first answer is the one you usually get from CSE or government ministers and members of parliament—often these exact words. This prohibition is indeed written into the

National Defence Act, not this precise formulation, but words to the same effect.

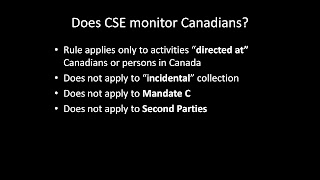

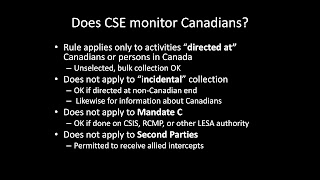

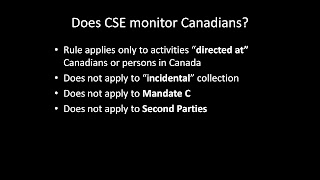

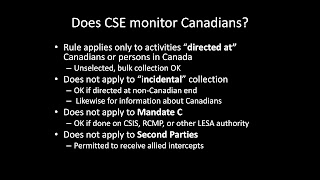

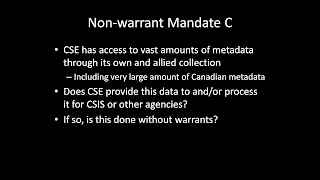

However, there are several important exceptions to this absolute-sounding rule:

First, the rule prohibits only activities "directed at" specific Canadians or persons in Canada. Thus, for example, bulk collection of metadata, because it is not collected with any specific target in mind, is permitted—even if, as in the "

Airport wi-fi" case, all of the metadata in question relates to persons in Canada.

"Incidental" collection of Canadian communications (collected when one of CSE's foreign targets communicates with a Canadian) is also permitted.

Targeted collection of Canadian communications is permitted under Mandate C (i.e., when a federal

law enforcement or security agency requests such collection and has lawful authority for the request).

Finally, CSE is permitted to receive Canadian communications collected and forwarded by its SIGINT allies, although it is not permitted to request the targeting of Canadians. CSE recently

formalized procedures for providing such intercepts to CSIS.

None of these exceptions opens the door to unlimited mass surveillance of all Canadians, and such information as we have suggests that the amount of Canadian-related information collected by CSE is, with the exception of metadata, mostly very limited.

But the information we have is itself very incomplete, and a surprisingly large amount of legal surveillance could be hidden behind the details that remain redacted.

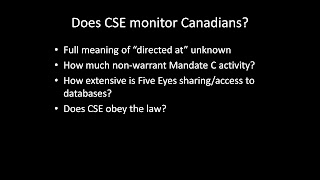

This leads to my third answer: We don't know.

We don't know the full meaning of "directed at" as the government understands the term. CSE modified its activities following a

2012 court case that rejected an attempt by CSIS to broaden the meaning of the term, which suggests that, at that time at least, CSE was operating with an excessively permissive understanding of its meaning.

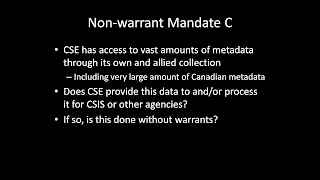

An unknown amount of activity could also be underway to analyze metadata or other non-content data on behalf of CSIS or the RCMP. Such processing might fall beneath the threshold considered to require a judicial warrant, and thus would be subject to much less stringent limits. Canadian communications that are not considered "private communications" under the

Criminal Code might also be subject to looser rules.

The potential for larger-than-realized access to Canadian-related information through allied collection and sharing also needs to be recognized.

Finally, it might also be questioned whether CSE actually obeys the various rules that limit the extent to which it is legally permitted to monitor Canadians.

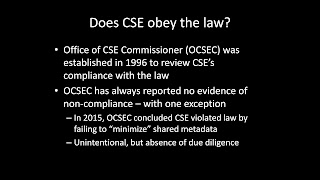

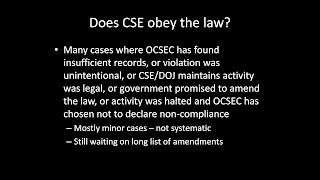

This leads to my next question: Does CSE obey the law?

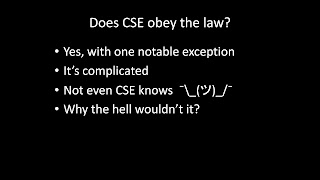

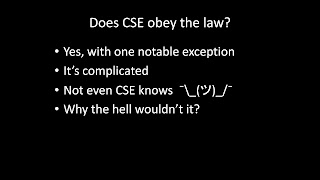

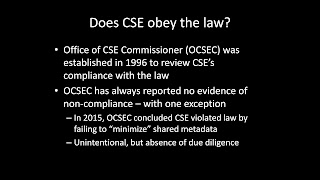

I have four answers to this question.

The notable exception occurred in 2015 when the CSE Commissioner declared CSE in violation of the law. (The decision was

reported to the public in 2016).

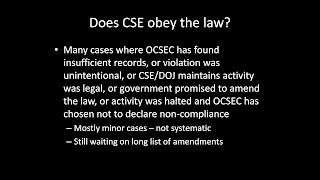

The complications arise because not every instance in which CSE fails or may have failed to follow legal requirements is assessed by the Commissioner as formal non-compliance (see my somewhat tongue in cheek discussion

here).

Here's the short explanation of that.

It's worth noting that these are mostly fairly minor incidents. There's no systematic program of monitoring Canadians hiding among these items, although some of the disagreements over legal interpretations do touch on CSE's core activities.

Over the years, CSE Commissioners have recommended a long list of amendments that would clear up these interpretation issues and place CSE on a sounder legal footing. The government promised action on a number of amendments as long ago as 2007, but nine years later we're still waiting.

A broader question relates to uncertainties in the proper interpretation of the laws that pertain to CSE's activities. In this respect, not even CSE really knows if it obeys the law. In many cases, the courts have simply not addressed these questions.

This could change as a result of the

BCCLA and

CCLA court challenges currently underway.

My final thought with respect to CSE and the law is, why wouldn't we expect it obey the law (at least, as the agency understands it)?

There is every reason to believe that compliance with the law is a fundamental part of CSE's ethos, and if the government wanted the agency to do something not currently legal, it could probably manage to make it legal. It's the government that writes the laws after all, although that power is somewhat checked by the courts.

The question of whether the government will grant itself additional "

lawful access" powers is currently back on the parliamentary agenda.

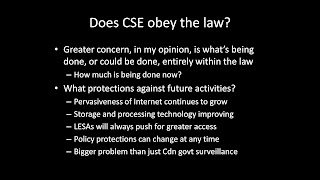

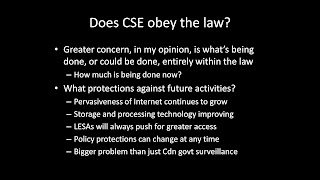

The question of compliance with the law is certainly important.

But, for me, the greater concern is what's being done, or could be done, entirely within the law. Is the line that defines activities permitted by the law in the right place?

It may be that CSE's activities related to Canadians are comparatively minor and tightly constrained. But they might also be quite a lot larger than the information that is currently public suggests. We just don't know.

And the potential for excessive, intrusive surveillance will only grow in the future.

Which leads to my final question: How can we protect Canadians?

I don't have a lot of answers to this question.

But I don't think we can rely on "sunny ways".

(The photo shows Prime Minister Trudeau addressing CSE employees at the Edward Drake Building in June 2016. To the best of my knowledge, this was the first time a prime minister visited CSE.)

[

Update 12 February 2017: Actually, John Diefenbaker visited the agency in October 1959.]

A number of proposals have been made to improve the oversight/review mechanisms and reform the legal regime pertaining to CSE and other members of the Canadian intelligence community.

But other people in this room could describe the merits of these proposals much better than I could.

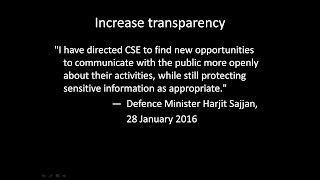

Instead, I would like to focus the remaining portion of this talk on possibilities for increasing transparency around CSE and its activities.

Greater transparency would be useful not only to create a more informed public, but also to maintain the "social license" that CSE and other elements of the Canadian intelligence community need in order to operate.

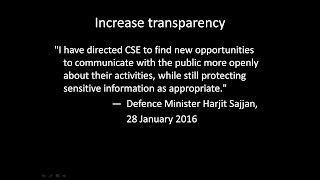

CSE’s minister agrees with me that greater transparency is desirable.

However, the main change so far has been the creation of a CSE Twitter account.

I have a short list of other suggestions.

Parliamentary testimony is one of the only sources of information about CSE plans, policies, and operations.

But it has been of very limited usefulness so far.

Parliamentarians are rarely informed enough to ask good questions; government members mostly spend their time trying to make the government look good; and testimony takes place in open sessions, so CSE witnesses are very limited in what they are willing to say.

Even when questions are good, the answers may be less than satisfactory.

This question by MP Elaine Michaud is a good example. In his answer, CSE Chief John Forster wouldn't even confirm that metadata sharing takes place. As it turns out, this question was asked on the very day that CSE suspended its Internet metadata sharing with its Five Eyes partners as a result of the minimization problem.

But Forster certainly wasn't going to talk about that. Defence Minister Nicholson, who was sitting beside him, hadn't even been told yet, and this wouldn't have been the best way for him to find out.

The Committee of Parliamentarians proposed in Bill C-22 is likely to improve this situation somewhat. But the government's proposal has serious limitations. And if most of the committee's sessions end up

in camera, the public may end up learning even less than now.

The government should commit to establishing a properly informed committee and ensure the maximum possible availability of information to the public.

Bottom line: Parliamentary testimony is a limited source of transparency. It might get better in the future, but it might get worse.

Proactive disclosure: CSE was exempted from the government’s proactive disclosure policy.

One could dispute aspects of that decision, but that's not my primary concern here.

I am more interested in other information that CSE could choose to make available proactively. CSE does do this occasionally, notably on its

website, but it could do much, much more.

For example, this kind of

Questions and Answers document, prepared to help the CSE Chief answer possible questions during testimony, could be routinely released.

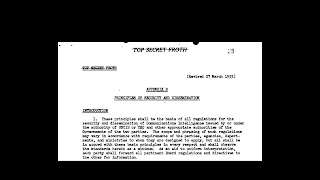

Many historical documents, such as the Canada-U.S. CANUSA Agreement, could also be proactively released. The U.S.-U.K. equivalent of the CANUSA Agreement, the

UKUSA Agreement, was declassified and posted on the web in 2010.

This

CANUSA appendix was released by NSA, apparently by mistake, in 2015, but the rest of the CANUSA agreement remains inexplicably unreleased.

[Update 23 April 2017: The

CANUSA Agreement was finally released in April 2017 following an Access to Information request.]

Bottom line: Proactive disclosure could be greatly improved.

Access to Information (ATI) responses: ATI responses can be quite useful, but most are very heavily redacted.

We get a lot of

this sort of thing, or worse – it's not unusual to see page after page entirely blanked out. Some of this is justified, of course. CSE does have legitimate secrets that it needs to keep.

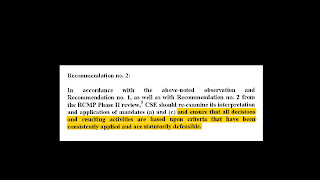

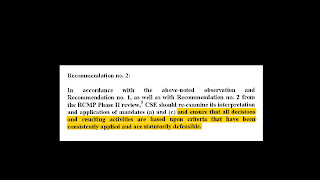

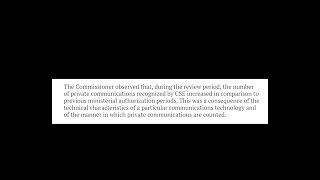

But sometimes there is no justification for the redaction at all. In this example, we eventually did find out what was redacted from this recommendation made by the CSE Commissioner.

Here’s what it said.

The implication that CSE may not have been ensuring that its decisions and activities were based on consistently applied and statutorily defensible criteria is embarrassing to the agency, yes, but there was absolutely no national security justification for withholding this information.

No one knows how often this kind of entirely unjustified, and probably unlawful, redaction is made.

Bottom line: ATI responses are an important source of information, but there is much room for improvement.

Annual Report: CSE could publish a voluntary annual report (like CSIS does), and also an annual Departmental Performance Report or equivalent. Such information used to be reported in the DND Departmental Performance Report.

This example from DND's 2001-02 Departmental Performance Report was 3 pages long. It included budget figures broken down into salary & personnel, operations & maintenance, and capital. Staffing numbers were provided. The section also contained explanatory text on CSE's plans and priorities.

This detailed reporting all stopped in 2011 when CSE became a stand-alone agency. There is no CSE Departmental Performance Report, and no formal or informal annual report.

No justification has ever been provided as to why this information can no longer be released. Basic budget figures are still reported in Main Estimates and the annual Public Accounts of Canada publications, but detailed information is no longer provided.

Bottom line: Transparency has almost entirely disappeared in this respect.

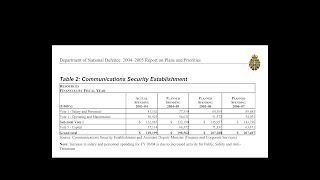

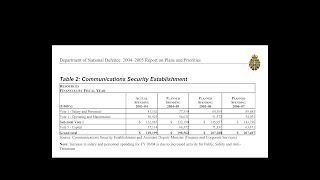

Estimates, Part III (Report on Plans and Priorities): Similar information also used to be reported in a 1- to 2-page section of the DND Report on Plans and Priorities.

This example from the 2004-05 RPP showed planned spending not only for the coming year but for each of the 2 following years as well. The figures were again broken down into salary & personnel, operations & maintenance, and capital. Additional explanatory information was provided.

This RPP reporting also ended when CSE became a stand-alone agency. Capital spending numbers are no longer available anywhere.

Bottom line: Transparency has almost entirely disappeared here as well. Again without any justification provided.

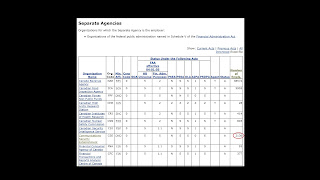

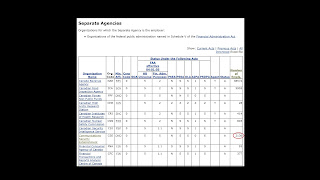

Staff numbers: Until February 2016, updated staff numbers were published every month for all departments and agencies of the government, including CSE. This practice has now stopped.

In February 2016, CSE had 2136 employees. Staffing information is no longer published anywhere.

Bottom line: CSE has gone entirely dark on this subject. Why can’t CSE publish these numbers itself?

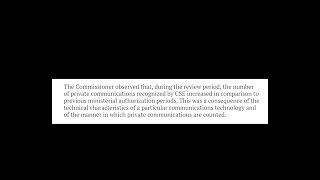

Finally, there's the OCSEC annual report: CSE has no formal censorship power over the contents of this report, but it does have control over the classification and declassification of information, which gives it very significant

de facto censorship power. CSE can't stop the Commissioner from talking about a particular subject, but it can certainly reduce his comments to barely comprehensible gibberish.

When the rate at which CSE used or retained Canadian private communications collected under its Mandate A went up 4410% last year, this was all the explanation the Commissioner could give.

Allowing the Commissioner to make more complete and detailed explanations would substantially increase the value of those reports, and probably serve to reduce the level of suspicion many Canadians feel about CSE.

Although there is excessive secrecy in the U.S. as well as in Canada, in most respects the U.S. provides much more detailed information about NSA operations than Canada does about CSE.

See, for example, this information about U.S. identities in SIGINT reporting. (Source:

Statistical Transparency Report Regarding Use of National Security Authorities - Annual Statistics for Calendar Year 2015, May 2, 2016.)

Why can’t Canada at least meet this standard of transparency? Or indeed even go beyond it?

CSE should permit the release of much more information by OCSEC, including regular, detailed statistical information on the extent to which Canadian information is collected, processed, analyzed, and disseminated by or through CSE, including, for example, the number of Canadian identities (suppressed and unsuppressed) in CSE and allied reports issued during the year, the number of suppressed identities requested, and the number of identities revealed. Such data could be reported annually by OCSEC or by CSE through direct disclosure.

Bottom line: The information provided by OCSEC reports has been gradually increasing over the years, but major improvements are possible.

In all of these ways, CSE could increase transparency about its activities while still protecting necessary secrets. This would benefit both CSE and the Canadian public.

Thank you.

(End of presentation.)

And there you have it.

I went on for quite a bit longer than I probably should have, but my impression was that the talk was very well received.

CSE Deputy Chief (Policy and Communications) Dominic Rochon, who attended as a sort of respondent, sat through my extended harangue with very good grace. In the end he didn't directly address much of its content (in part no doubt because I left him little time), but he did acknowledge that CSE could do more to improve transparency about the agency. He promised specifically to look into releasing staff numbers.

His attendance at the event was itself arguably a step towards greater transparency. I thank him for participating.

My thanks also to everyone else who attended.

I also owe thanks to Professor Wesley Wark for inviting me to Ottawa to give the talk and to the staff at the University of Ottawa's Centre for International Policy Studies for organizing it.

Wesley and I have corresponded off and on for the last 25 years or so, but this was the first time we actually met.

I also had the great pleasure of meeting for the first time a number of other people I have worked with or shared information with over the years (in at least one other case, decades).

I obviously need to get out more often.

Update 29 November 2016: A couple of other points worth mentioning from Mr. Rochon's responses:

- CSE does not share the metadata it collects with other Canadian agencies, but certain CSE analytical work using metadata is shared with those agencies in the form of end-product reports.

- Except in certain cases, requests to CSE to reveal Canadian identity information that has been "suppressed" in CSE reports do not require a warrant.

- CSE does not support the idea of requiring a back-door in encryption systems.

Update 4 December 2016: A PDF document with the full set of PowerPoint slides is available

here.